Why Your Morning Coffee Timing Doesn't Matter (And What Does)

What the research actually shows about timing your caffeine

Andrew Huberman popularized the 90–120-minute caffeine delay across several 2021–2022 podcast episodes on caffeine & sleep.

Since then, it’s become even more controversial. But the issue is less about Huberman’s recommendation. After all, it’s a suggestion to test and I’ve found him consistently espousing the same principle we advocate for so strongly here: take what fits, leave what doesn’t.

Over time however, many mistook suggestions for universal laws and parroted the protocol without accounting for individual nuance in neuroendocrine responses.

Now it’s time to discern the truth.

The Mechanistic Basis of the Claims

The caffeine delay protocol rests on three mechanisms.

Mechanism #1: Prevention of Afternoon Energy Crashes

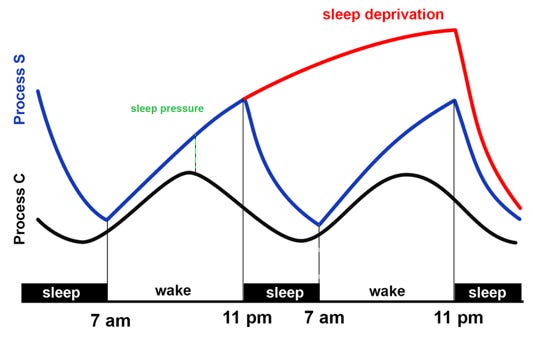

While you’re awake, adenosine accumulates in your brain as a metabolic byproduct. This buildup creates homeostatic sleep pressure — your brain’s internal timer tracking how long you’ve been conscious.

More time awake → more adenosine → eventual fatigue by evening

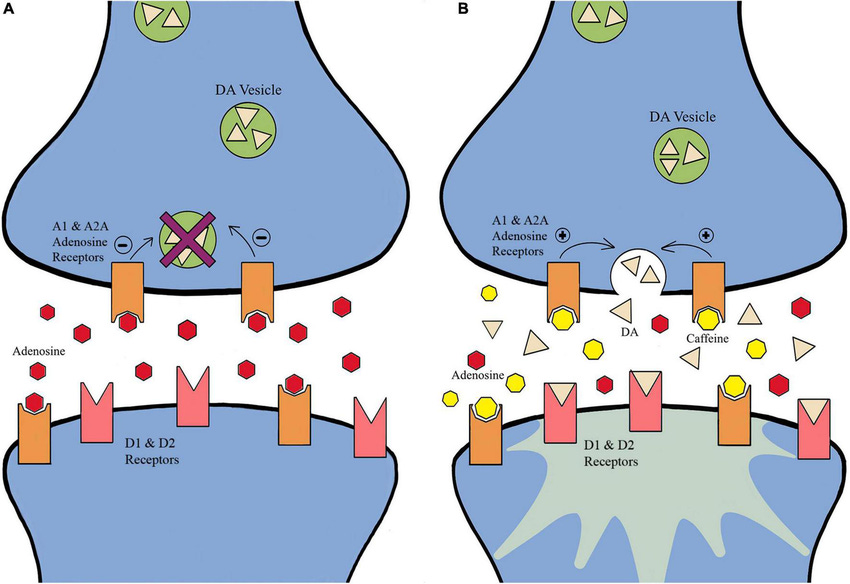

Caffeine works by blocking adenosine receptors1 (A1 & A2A), preventing adenosine from inhibiting arousal neurons. As a result, we get: amplified dopamine release, enhanced glutamatergic transmission, heightened alertness, & improved cognitive performance.

The concept behind delaying morning caffeine is such that upon waking, residual adenosine from sleep lingers. Immediate caffeine blocks receptors without clearing this buildup and masking it. With a 5–6 hr half-life, caffeine clears by midday. As it exits, you face both residual sleep adenosine plus newly accumulated adenosine.

Mechanism #2: Regulation of Cortisol Rhythms

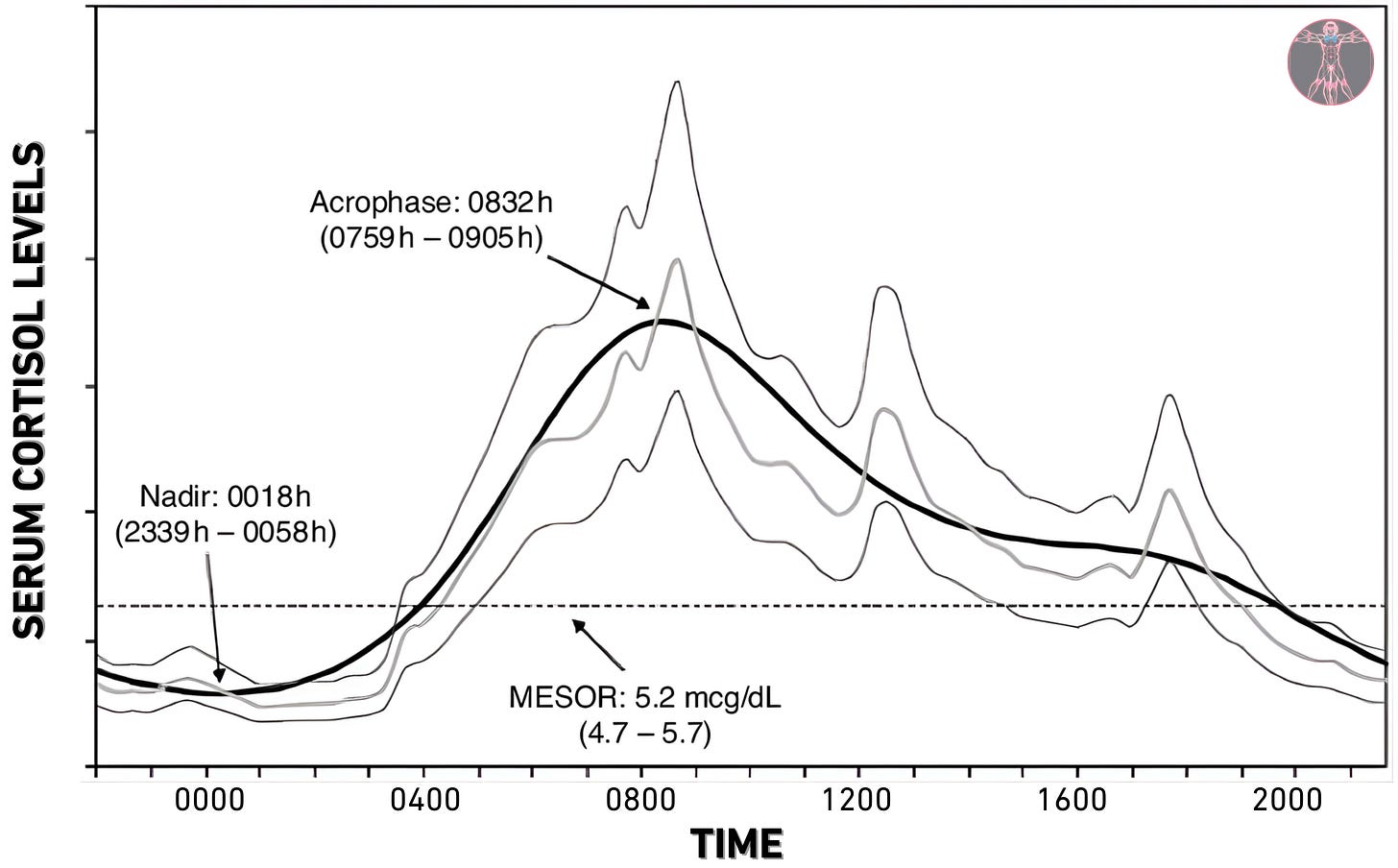

Cortisol follows a circadian rhythm2. It bottoms out during early sleep, then surges upon waking in what is referred to as the cortisol awakening response (CAR). This natural spike can double baseline levels within 30–45 minutes of waking.

Caffeine stimulates cortisol release by removing adenosine’s inhibitory brake on the HPA axis, increasing CRH and downstream ACTH/cortisol production.

Immediate post-wake caffeine may excessively amplify the CAR. Chronic over-amplification can flatten your diurnal cortisol curve and promote glucocorticoid receptor downregulation. This is the essence of cortisol resistance.

Waiting hypothetically allows the CAR to peak naturally without caffeine interference. By mid-morning, cortisol enters its natural trough. Introduce caffeine then for a secondary boost without compounding HPA stress or accelerating receptor tolerance.

Mechanism #3: Improved Sleep & Long-Term Tolerance

The final mechanism works indirectly by reducing the need for compensatory afternoon dosing that would otherwise interfere with evening sleep.

Immediate morning caffeine blocks adenosine at its daily low accelerating receptor upregulation with 10–50% increased adenosine receptor density. This drives tolerance and creates a sharper afternoon adenosine rebound when caffeine clears worsening fatigue and prompting late-day caffeine doses that disrupt sleep.

Delaying caffeine theoretically slows this adaptation cycle, reducing tolerance buildup and the need for afternoon re-dosing.

Let’s step away from the mechanisms & look at what the evidence states.

What The Evidence Suggests

Cortisol & Timing

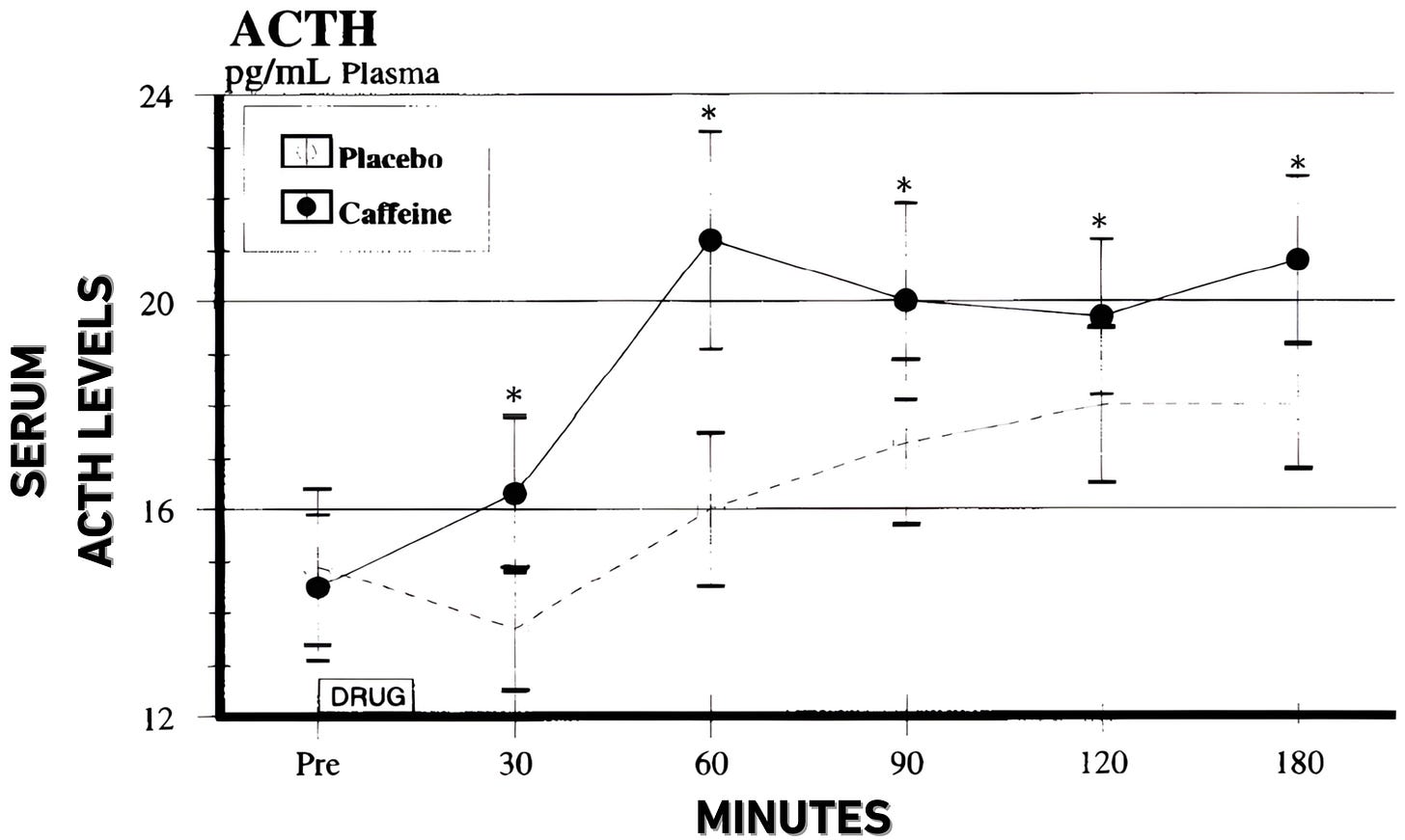

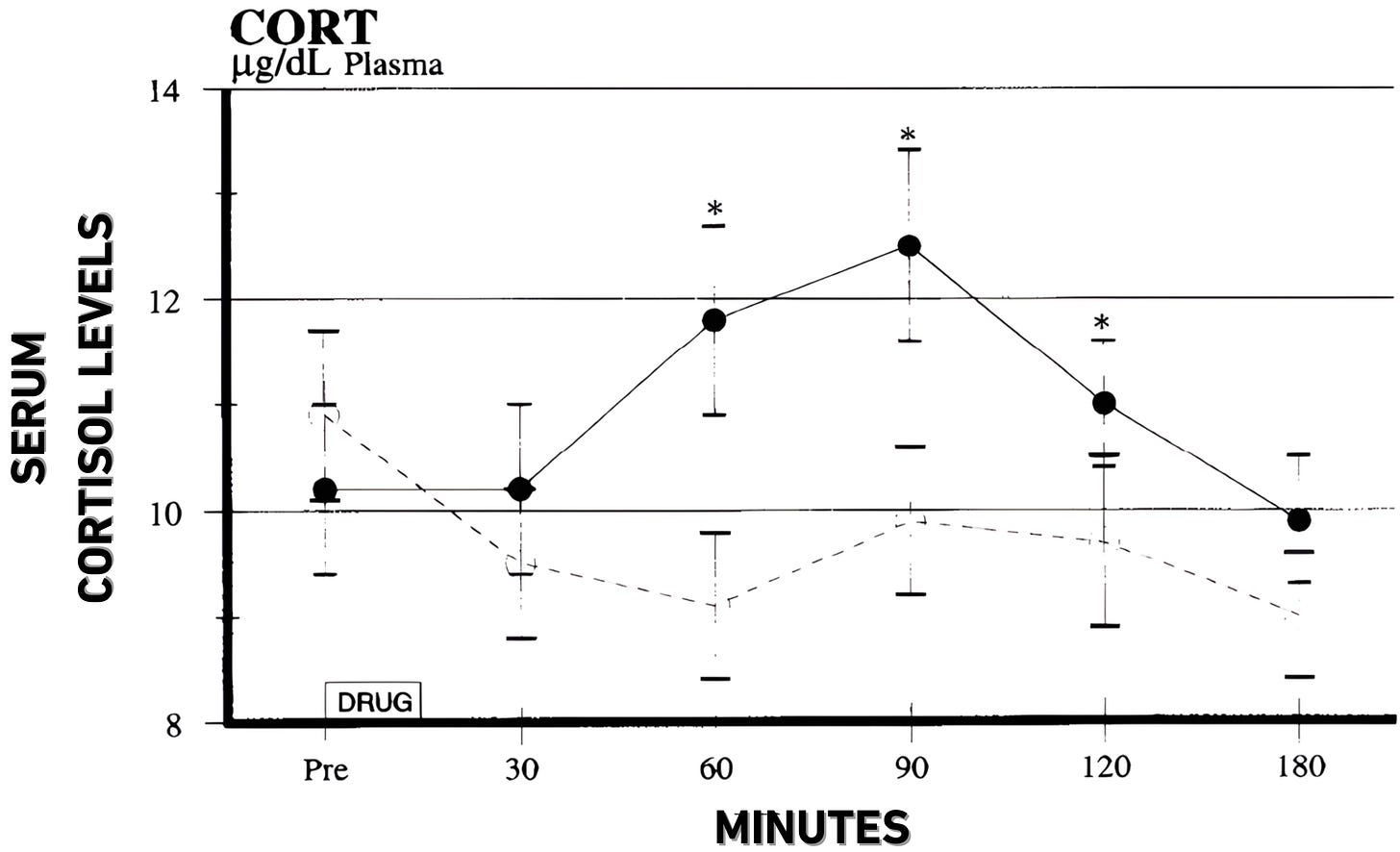

Lovallo et al. (1995)3 administered morning caffeine at 3.3 mg/kg (not immediately upon waking) and found relative to placebo:

ACTH increased 33%

Cortisol rose 30%

Delaying intake did not prevent caffeine’s cortisol-stimulating effect.

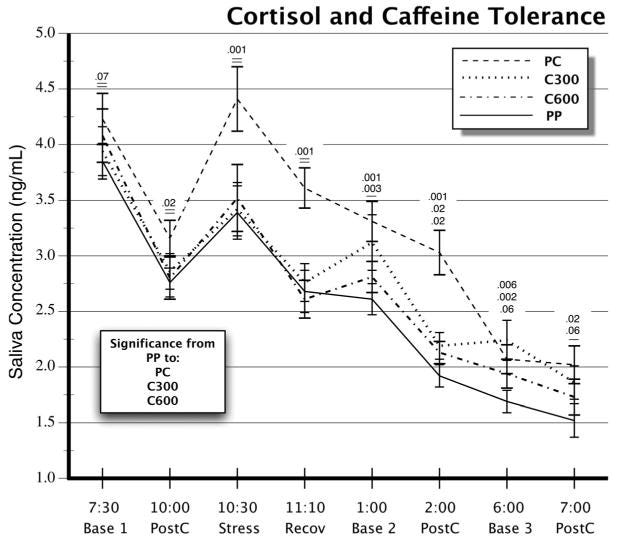

In a 4-week randomized, double-blind crossover trial, Lovallo et al. (2005), showed acute caffeine elevated cortisol in abstinent individuals, but habitual use blunted this response. After 5 days of abstinence, caffeine significantly increased cortisol throughout the day. After 5 days of moderate (300 mg/day) or high (600 mg/day) intake, the morning cortisol response to 9:00 AM caffeine was blunted.

Habitual intake level (not timing) moderates cortisol response.

This tolerance develops even at lower doses. Rieth et al. (2016) observed the same blunting effect at 200 mg daily.

Adenosine Dynamics

The afternoon crash theory assumes adenosine continues declining for 90–120 minutes after waking, however mechanistic logic suggests it doesn’t.

Adenosine increases rapidly within minutes4 of the sleep-to-wake transition, then stabilizes across waking hours. During sleep5, the inverse occurs: adenosine drops quickly in the first hours, then plateaus. By morning, adenosine has cleared and immediately begins accumulating again upon waking.

N = 5 Testing

Coffee expert James Hoffmann conducted a 30-day blind experiment. Five subjects drank either caffeinated or decaf coffee each morning without knowing which, logged all caffeine intake, and completed fatigue questionnaires and reaction-time tests. Sleep was tracked to assess timing effects.

No significant difference in afternoon tiredness or alertness emerged between delayed and immediate caffeine days.

Link to the full video below:

Why Genetics & Individuality Matter Most

Genetics

Genetic polymorphisms determine how you process and respond to caffeine.

CYP1A2: The rs762551 polymorphism6 divides people into fast (A/A = 45% of population), intermediate (A/C = 45% of population), & slow (C/C = 10% of population) metabolizers. Fast metabolizers clear caffeine up to 40% quicker: 2–4 hour half-life versus 5–7 hours for slow metabolizers. Slow metabolizers might experience prolonged effects from morning caffeine → more likely to have afternoon crashes or sleep disruptions → better alignment to delaying intake..

ADORA2A: The rs5751876 variant7 modulates adenosine receptor sensitivity. C/C homozygotes show heightened sleep disturbances and reduced slow-wave activity after caffeine suggesting they benefit more from delayed intake to preserve sleep quality.

Individual Factors

Epigenetics: Habitual coffee consumption alters DNA methylation patterns8 affecting genes involved in metabolism and immune function.

Sleep quality: Chronic sleep restriction heightens adenosine sensitivity9. making delayed intake ideal to capitalize on natural buildup and avoid exacerbating tolerance.

Autonomic nervous system balance: Stress levels interact via the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. High baseline cortisol10 might render immediate caffeine redundant or anxiogenic, supporting delay to prevent additive effects.

Body composition: Obesity prolongs caffeine half-life up to 70%11.

Diet: Certain foods impact caffeine metabolism. Grapefruit juice decreases clearance by 23% & extends half-life by 31%12. Consumption of cruciferous vegetables13 & large quantities of vitamin C14 increase caffeine clearance.

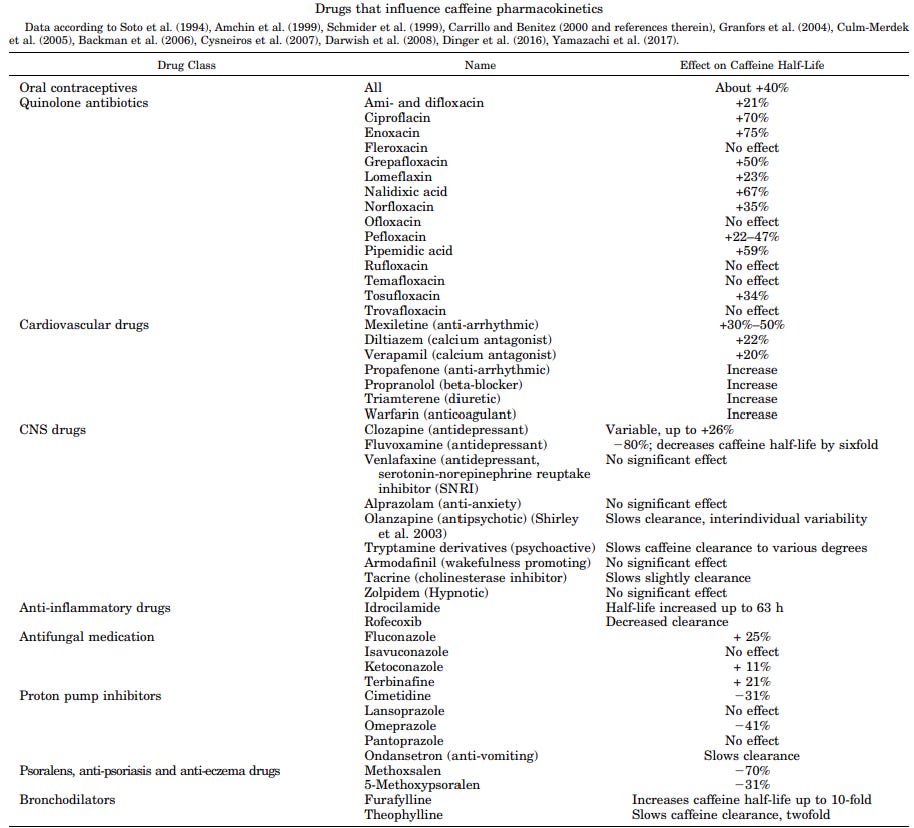

Drugs: Various drugs15 significantly alter caffeine half-life.

The Verdict: Should You Delay Morning Caffeine?

Alright — let’s summarize it all.

Short Answer

For most people, delaying caffeine 90–120 minutes after waking provides minimal to no benefit. The evidence doesn’t support the proposed mechanisms as universal truths. Though — context & biochemical individuality are paramount.

Who Might Benefit From Delaying

Slow CYP1A2 metabolizers (C/C or A/C genotype) clear caffeine 40% slower than fast metabolizers. Delaying intake may better align caffeine’s effects with their circadian rhythm and reduce cumulative exposure.

High ADORA2A sensitivity individuals (C/C homozygotes at rs5751876) experience greater sleep disruption from caffeine. They may benefit from delayed intake to minimize interference with adenosine signaling & preserve sleep quality.

Chronic sleep restriction individuals show heightened adenosine sensitivity. Delaying caffeine could theoretically provide better symptom relief by targeting periods of higher adenosine accumulation, though direct evidence is lacking.

High-stress/anxious individuals with elevated baseline cortisol could find immediate caffeine redundant or anxiety-provoking. Waiting until cortisol naturally declines mid-morning could prevent additive HPA activation.

Who Shouldn’t Bother

Fast CYP1A2 metabolizers (A/A genotype) clear caffeine quickly (2–4 hour half-life). Immediate morning consumption poses minimal afternoon crash or evening interference risk.

Low-to-moderate consumers (<300 mg/day) develop less pronounced tolerance & epigenetic changes.

Consistent, circadian-aligned sleepers who maintain dialed-in sleep schedules & quality show no compelling reason to delay intake.

If you function optimally with immediate caffeine — no need to create solutions to problems you don’t have. Individual response > theoretical mechanisms.

What likely matters more than timing:

Total daily dose

Habitual intake/tolerance

Genetic profile as it relates to caffeine metabolism

Sleep quality

Baseline stress/anxiety levels

Test. Assess. Retest.

Take what fits. Leave what doesn’t

Stay after it until next week.

Your friend,

Phys

Sogard AS, Mickleborough TD. The therapeutic potential of exercise and caffeine on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in athletes. Front Neurosci. 2022 Aug 12;16:978336. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2022.978336. PMID: 36033633; PMCID: PMC9412016.

Chan S, Debono M. Replication of cortisol circadian rhythm: new advances in hydrocortisone replacement therapy. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2010 Jun;1(3):129-38. doi: 10.1177/2042018810380214. PMID: 23148157; PMCID: PMC3475279.

Lovallo WR, Al’Absi M, Blick K, Whitsett TL, Wilson MF. Stress-like adrenocorticotropin responses to caffeine in young healthy men. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1996 Nov;55(3):365-9. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00105-0. PMID: 8951977.

Basheer R, Strecker RE, Thakkar MM, McCarley RW. Adenosine and sleep-wake regulation. Prog Neurobiol. 2004 Aug;73(6):379-96. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2004.06.004. PMID: 15313333.

Dworak M, McCarley RW, Kim T, Kalinchuk AV, Basheer R. Sleep and brain energy levels: ATP changes during sleep. J Neurosci. 2010 Jun 30;30(26):9007-16. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1423-10.2010. PMID: 20592221; PMCID: PMC2917728.

Yang A, Palmer AA, de Wit H. Genetics of caffeine consumption and responses to caffeine. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2010 Aug;211(3):245-57. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1900-1. Epub 2010 Jun 9. PMID: 20532872; PMCID: PMC4242593.

Fulton JL, Dinas PC, Carrillo AE, Edsall JR, Ryan EJ, Ryan EJ. Impact of Genetic Variability on Physiological Responses to Caffeine in Humans: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2018 Sep 25;10(10):1373. doi: 10.3390/nu10101373. PMID: 30257492; PMCID: PMC6212886.

Chuang YH, Quach A, Absher D, Assimes T, Horvath S, Ritz B. Coffee consumption is associated with DNA methylation levels of human blood. Eur J Hum Genet. 2017 May;25(5):608-616. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2016.175. Epub 2017 Feb 15. PMID: 28198392; PMCID: PMC5437893.

Kim Y, Elmenhorst D, Weisshaupt A, Wedekind F, Kroll T, McCarley RW, Strecker RE, Bauer A. Chronic sleep restriction induces long-lasting changes in adenosine and noradrenaline receptor density in the rat brain. J Sleep Res. 2015 Oct;24(5):549-558. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12300. Epub 2015 Apr 21. PMID: 25900125; PMCID: PMC4583343.

Raza ML, Haghipanah M, Moradikor N. Coffee and stress management: How does coffee affect the stress response? Prog Brain Res. 2024;288:59-80. doi: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2024.06.013. Epub 2024 Jul 15. PMID: 39168559.

Abernethy DR, Todd EL. Impairment of caffeine clearance by chronic use of low-dose oestrogen-containing oral contraceptives. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1985;28(4):425-8. doi: 10.1007/BF00544361. PMID: 4029248.

Fuhr U, Klittich K, Staib AH. Inhibitory effect of grapefruit juice and its bitter principal, naringenin, on CYP1A2 dependent metabolism of caffeine in man. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1993 Apr;35(4):431-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1993.tb04162.x. PMID: 8485024; PMCID: PMC1381556.

Lampe JW, King IB, Li S, Grate MT, Barale KV, Chen C, Feng Z, Potter JD. Brassica vegetables increase and apiaceous vegetables decrease cytochrome P450 1A2 activity in humans: changes in caffeine metabolite ratios in response to controlled vegetable diets. Carcinogenesis. 2000 Jun;21(6):1157-62. PMID: 10837004.

Trang JM, Blanchard J, Conrad KA, Harrison GG. The effect of vitamin C on the pharmacokinetics of caffeine in elderly men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1982 Mar;35(3):487-94. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/35.3.487. PMID: 7064899.

Nehlig A. Interindividual Differences in Caffeine Metabolism and Factors Driving Caffeine Consumption. Pharmacol Rev. 2018 Apr;70(2):384-411. doi: 10.1124/pr.117.014407. Epub 2018 Mar 7. PMID: 29514871.

“With a 5–6 hr half-life, caffeine clears by midday.” No, by midday you have half the caffeine you drank still in your system, and 5-6 hours after that 1/4. If you drink a couple cups in the morning (keep in mind a “cup” of coffee is only 150ml), you’re going to bed at night with 1/4 of coffee in your system. No wonder everybody’s sleep is f’d.

Quitting coffee and caffeine was the single best thing I ever did to improve sleep. Absolute game-changer (although the withdrawals were awful, the worst of any substance I’ve ever experienced).